New discovery that can make a dielectric elastomer joint bend up and down demonstrates its potential in soft robotic applications as lightweight, energy-efficient flapping wings.

From the Journal: Applied Physics Letters

Washington, D.C., March 31, 2015 — Dielectric elastomers are novel materials for making actuators or motors with soft and lightweight properties that can undergo large active deformations with high-energy conversion efficiencies. This has made dielectric elastomers popular for creating devices such as robotic hands, soft robots, tunable lenses and pneumatic valves — and possibly flapping robotic wings.

Reporting this week in the journal Applied Physics Letters, from AIP Publishing, researchers from the Harbin Institute of Technology in Weihai, China and the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), have discovered a new resonance phenomenon in a dielectric elastomer rotary joint that can make the artificial joint bend up and down, like a flapping wing.

“The dielectric elastomer is a kind of electro-active polymer that can deform if you apply a voltage on it,” said Jianwen Zhao, an associate professor of the Department of Mechanical Engineering at the Harbin Institute of Technology. He said that most studies on dielectric elastomers are using a static or stable voltage to stimulate the joint motion, which makes the joint bend at a fixed angle, while they are interested in seeing how the artificial joint react to an alternating or periodically changing voltage.

“We found that alternating voltages can make the joint continuously bend at different angles. Especially, when the rotational inertia of the joint or the applied voltage is large enough, the joint can deform to negative angles, in other words, it can bend beyond 90 degrees to 180 degrees, following a principle different from the normal resonance rule.”

Zhao said this new phenomenon makes the dielectric elastomer joint a good candidate for creating a soft and lightweight flapping wing for robotic birds, which would be more efficient than bird wings based on electrical motors due to the higher energy conversion efficiency (60 to 90 percent) of the dielectric elastomer.

Muscle-like Actuators

Soft robotics provides many advantages compared to traditional robotics based on rigid materials, including safer physical human-robot interactions, more efficient/stable locomotion and adaptive morphologies. Dielectric elastomers, due to their soft and lightweight inherent properties and superior electro-mechanical performances, are considered as a kind of material close to human muscles, attracting wide attention among soft-technology scientists in recent years.

Made by sandwiching a soft insulating elastomer film between two compliant electrodes, dielectric elastomers can be squeezed and expanded in a plane when a voltage is applied between electrodes. In contrast to actuators based on rigid materials such as silicon, dielectric elastomers can reach a very large extent of stretch, often exceeding 100 percent elongation while not breaking, enabling new possibilities in many fields including soft robotics, tunable optics, and cell manipulation.

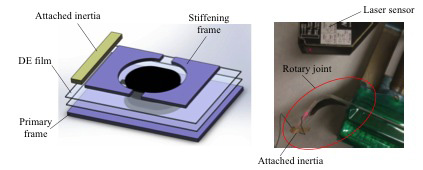

The dielectric elastomer actuator Zhao used is called a “dielectric elastomer minimum-energy structure,” which is composed of a thin elastic frame and pre-stretched dielectric elastomer films, Zhao said. After adhering the pre-stretched film to the thin elastic frame, the restoring force of the dielectric elastomer film bends the elastic frame, balancing at a minimum energy state.

When applying kilovolts of low-current electricity on the dielectric elastomer, the frame flattens out and the bending angle decreases. To restrict frame bending to only one axis, two stiffening frames are mounted to the primary frame as rigid non-bending edges, the whole thing then forms a rotary joint. Dynamically changing the voltage can dynamically change the joint angle, which makes dielectric elastomer minimum-energy structures a useful structure for fabricating soft devices, Zhao said.

A New Oscillation Phenomenon Found

In Zhao’s experiment, the researchers stimulated the motion of the rotary joint using an alternating, square-wave voltage, i.e. a voltage with a fixed value that is periodically turned on and off, which is different from the practice of previous scientists, who “usually use static or stable voltage to study the joint motion.”

“The advantage of alternating voltages is that they shift between different values, thus helping us continuously manipulate the joint’s bending angles.” Zhao said.

“The advantage of alternating voltages is that they shift between different values, thus helping us continuously manipulate the joint’s bending angles.” Zhao said.

The new practice also stimulated new results. After experimenting with various parameters such as voltage values, frequencies and the joint mass in the dielectric elastomer joint system, Zhao and colleague observed a new resonance phenomenon: When the rotational inertia of the joint is large enough or the applied voltage is high enough, the joint can bend up and down like a flapping wing, reaching a bending angle over 90 degrees or what the researchers call negative angles.

“When the joint realizes negative angles, its motion will become more complicated, following a special resonance rule different than the normal one, which we call nonlinear oscillation,” he said.

In normal resonance, the joint bends following the voltage frequency, and will reach the largest bending angle when the joint’s inherent frequency is equal to the voltage frequency, Zhao explained. While in nonlinear oscillation, the joint reaches its largest bending angle when the provide voltage frequency is near but smaller than twice the joint’s natural frequency. Meanwhile, the joint amplitude (the bending scope) is also larger than in normal resonance, indicating a larger lift force in the special resonance.

This new phenomenon and the principle, Zhao noted, may open doors for many novel soft devices, such as soft and lightweight robots for circumstances with restricted space and weight requirements or flapping wings of soft robotic birds that can generate a large lift force. Also, since dielectric elastomers feature high energy density (seventy times higher than conventional electromagnetic actuators) and high-energy conversion efficiency (60 to 90 percent), they could be good candidates for making energy-efficient devices, Zhao said.

The researchers’ next step is to improve the function of the dielectric elastomer rotary joint and refine the fabrication technique to make a real flapping wing.

###

Article Title

Authors

Jianwen Zhao, Junyang Niu, David McCoul, Zhi Ren and Qibing Pei