High-Speed Photography Provides First Direct Evidence of How Microbubbles Dissolve Killer Blood Clots

From the Journal: Applied Physics Letters

WASHINGTON, D.C. Dec. 13, 2013 — Ultrasound-stimulated microbubbles have been showing promise in recent years as a non-invasive way to break up dangerous blood clots. But though many researchers have studied the effectiveness of this technique, not much was understood about why it works. Now a team of researchers in Toronto has collected the first direct evidence showing how these wiggling microbubbles cause a blood clot’s demise. The team’s findings are featured in the AIP Publishing journal Applied Physics Letters.

WASHINGTON, D.C. Dec. 13, 2013 — Ultrasound-stimulated microbubbles have been showing promise in recent years as a non-invasive way to break up dangerous blood clots. But though many researchers have studied the effectiveness of this technique, not much was understood about why it works. Now a team of researchers in Toronto has collected the first direct evidence showing how these wiggling microbubbles cause a blood clot’s demise. The team’s findings are featured in the AIP Publishing journal Applied Physics Letters.

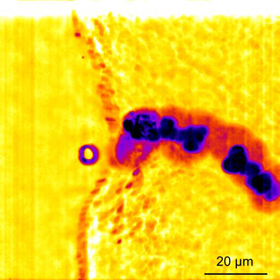

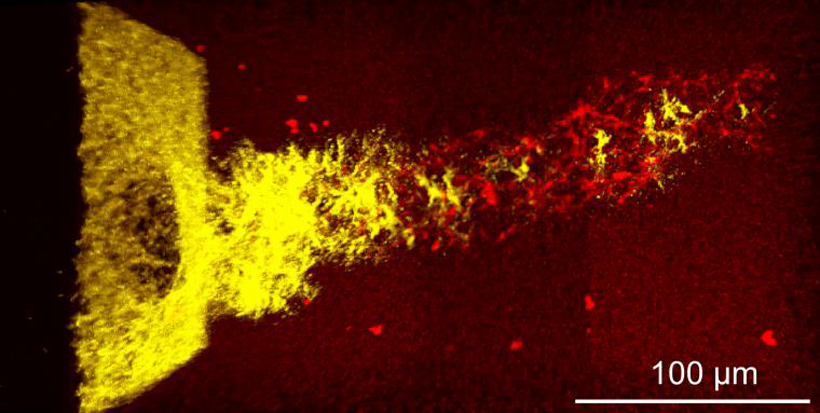

Previous work on this technique, which is called sonothrombolysis, has focused on indirect indications of its effectiveness, including how much a blood clot shrinks or how well blood flow is restored following the procedure. The Toronto team, which included researchers from the University of Toronto and the Sunnybrook Research Institute, tried to catch the clot-killing process in action. Using high-speed photography and a 3-D microscopy technique, researchers discovered that stimulating the microbubbles with ultrasonic pulses pushes the bubbles toward the clots. The bubbles deform the clots’ boundaries then begin to burrow into them, creating fluid-filled tunnels that break the clots up from the inside out.

These improvements in the understanding of how sonothrombolysis works will help researchers develop more sophisticated methods of breaking up blood clots, said lead author Christopher Acconcia.

Efforts so far “may only be scratching the surface with respect to effectiveness,” said Acconcia. “Our findings provide a tool that can be used to develop more sophisticated sonothrombolysis techniques, which may lead to new tools to safely and efficiently dissolve clots in a clinical setting.”

###

Article Title

Interactions between ultrasound stimulated microbubbles and fibrin clots

Authors

Christopher Acconcia, Ben Y. C. Leung, Kullervo Hynynen and David E. Goertz

Author Affiliations

University of Toronto and Sunnybrook Research Institute