From the Journal: American Journal of Physics

WASHINGTON, March 23, 2022 — Marinated, or pickled, eggs are enjoyed by cultures around the world. There are Pennsylvania Dutch red-beet pickled eggs, German-style ones with a heavy dose of mustard, and Asian recipes that use rice vinegar and soy sauce, to name a few.

The basis of any recipe is marinating hard boiled eggs in vinegar or brine, which cures the eggs by sufficiently saturating the egg whites via diffusion. In American Journal of Physics, published on behalf of the American Association of Physics Teachers by AIP Publishing, researchers at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln were inspired to demonstrate how diffusion works in an easy and quantifiable way.

“We wanted to develop an experiment for high school and college STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) students to show them how diffusion works in a simple visual manner and to ensure the experiment was easy to do at home so kids can learn diffusion on their own,” co-author Carson Emeigh said.

Driven by thermal energy, diffusion occurs when atoms, molecules, or other particles spread throughout a fluid (air or liquid) over time from the highest concentration point to the lowest. Diffusion is widely studied for myriad applications, from aircraft engines to drug development.

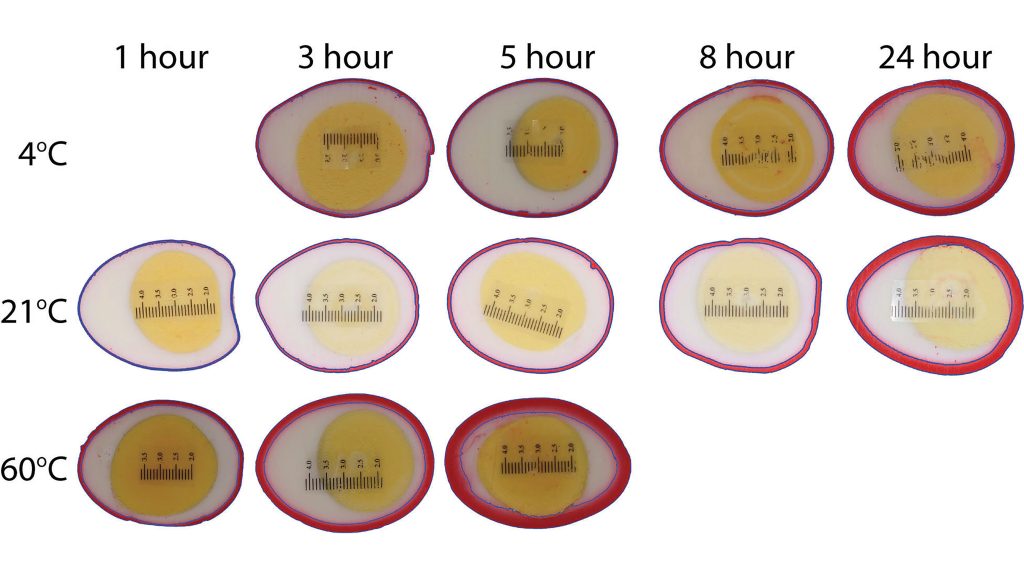

In their experiment, the researchers compared penetration levels of red food dye in the whites of peeled hard-boiled eggs at three different temperatures: refrigerator temperature (40 F), room temperature (70 F), and in a cool convection oven (140 F).

Each egg was taken out of the solution at a predetermined time (one hour, three hours, five hours, eight hours, or 24 hours), sliced in half with an egg slicer, and imaged. A digital camera on a tripod was placed above the light box.

The study demonstrated that at each increasing time interval, the dye diffused deeper into the egg white, with diffusion occurring more rapidly at higher temperatures.

The experiment can be simplified for home or classroom by using a pot or slow cooker instead of a convection oven, and eggs can be prepared in advance, so students can make all the measurements at the same time. Manual measurements of the penetration distance can replace the imaging method. Soy sauce or marinade of students’ choice could be used instead of food dye solution, allowing students to “taste” the differences in diffusion.

###

For more information:

Larry Frum

media@aip.org

301-209-3090

Article Title

Marinated eggs: An engaging quantitative demonstration of diffusion

Authors

Carson Emeigh, Hyeonggeun Luke Bak, Dilziba Kizghin, Haipeng Zhang, and Sangjin Ryu

Author Affiliations

University of Nebraska-Lincoln

American Journal of Physics

ABOUT THE JOURNAL

American Journal of Physics is devoted to the instructional and cultural aspects of physics. The journal informs physics education globally with member subscriptions, institutional subscriptions, such as libraries and physics departments, and consortia agreements. It is geared to an advanced audience, primarily at the college level. Contents include novel approaches to laboratory and classroom instruction, insightful articles on topics in classical and modern physics, apparatus, and demonstration notes, historical or cultural topics, resource letters, research in physics education, and book reviews.

ABOUT AAPT

AAPT is an international organization for physics educators, physicists, and industrial scientists—with members worldwide. Dedicated to enhancing the understanding and appreciation of physics through teaching, AAPT provides awards, publications, and programs that encourage teaching practical application of physics principles, support continuing professional development, and reward excellence in physics education. AAPT was founded in 1930 and is headquartered in the American Center for Physics in College Park, Maryland.