So-called Fröhlich condensation, a state in which protein molecules' vibrational modes coalesce at the lowest frequency, was first predicted almost five decades ago, but never experimentally demonstrated until now

From the Journal: Structural Dynamics

WASHINGTON, D.C., October 13, 2015 – If you take certain atoms and make them almost as cold as they possibly can be, the atoms will fuse into a collective low-energy quantum state called a Bose-Einstein condensate. In 1968 physicist Herbert Fröhlich predicted that a similar process at a much higher temperature could concentrate all of the vibrational energy in a biological protein into its lowest-frequency vibrational mode. Now scientists in Sweden and Germany have the first experimental evidence of such so-called Fröhlich condensation.

The researchers made the condensate by aiming terahertz radiation at a crystallized protein extracted from the white of a chicken egg. They report their results in the journal Structural Dynamics, from AIP Publishing and the American Crystallographic Association.

“Observing Fröhlich condensation opens the door to a much wider-ranging study of what terahertz radiation does to proteins,” said Gergely Katona, a senior scientist at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden. Terahertz radiation occupies the space in the electromagnetic spectrum between microwaves and infrared light. It has been proposed as a useful tool in applications ranging from airport security to cancer screening, but its effects on biological systems remains murky.

Katona said he is interested in studying how terahertz-induced Fröhlich condensation could change the rates of reactions catalyzed by biological enzymes or shift chemical equilibria. Such knowledge could lead to medical applications or new ways to control chemical reactions in industry, but Katona cautioned that the research is still at a fundamental stage.

As far as the safety implications for terahertz radiation, Katona said that the jury is still out. The effects he and his team observed are reversible and last only for a short time, he added.

The Long Path from Theory to Observation

The theoretical underpinnings of Fröhlich condensation are relatively simple, Katona noted. Fröhlich proposed that when proteins absorb a terahertz photon the added energy forces the oscillating molecules into a single, lowest-frequency mode. In contrast, other models predict that the protein will quickly dissipate the energy from the photon in the form of heat.

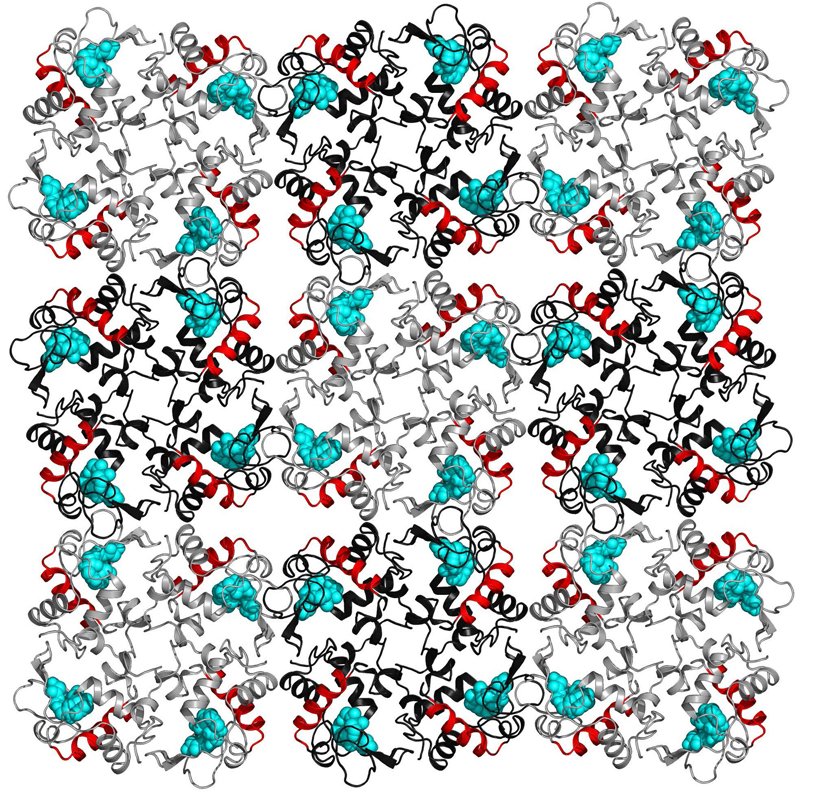

To distinguish between the two outcomes, Katona and his colleagues turned to a technique called X-ray crystallography. The technique works by irradiating a sample with X-rays. By studying how the X-rays scatter and interfere with each other, scientists can work out the relative density of electrons in different locations in the sample material, which can then be used to tell the position of atoms and molecules.

For their protein, the researchers chose the enzyme lysozyme, which is a common immune system protein that attacks the cell walls of invading bacteria. Previous studies had indicated that low-frequency vibrations (in the terahertz domain) strongly influence the function of the protein.

Katona and his colleagues aimed short bursts of 0.4 terahertz radiation at the lysozyme crystals while simultaneously gathering X-ray crystallography data. The researchers separated the data gathered when the terahertz radiation was on from the data gathered when it was off, and then statistically analyzed each set. They found evidence that one of the helix structures in the protein was compressed during terahertz radiation, and that the compression lasted on the order of micro- to milli-seconds, thousands of times longer than could be explained by the thermal dissipation model. The researchers concluded that the long-lasting structural changes could only be explained by Fröhlich condensation, a quantum-like collective state in which the molecules in a protein behave as one.

The real-world support for Fröhlich’s theory took so long to obtain because of the technical challenges of the experiment, Katona said.

“Terahertz radiation used to be very difficult to produce and is still difficult to handle,” he noted. Analyzing the X-ray data is also particularly challenging for low frequency vibrations, which are small in magnitude compared to typical structural changes in proteins.

The most important aspect of the experiment is that the researchers were able to detect structural changes in a protein that were not caused by heat dissipation, Katona said. Now that they’ve made the observations, the researchers are eager to explore how the structural changes affect the way the proteins work, he said.

###

For More Information:

Jason Socrates Bardi

jbardi@aip.org

240-535-4954

@jasonbardi

Article Title

Authors

Ida V. Lundholm, Helena Rodilla, Weixiao Y. Wahlgren, Annette Duelli, Gleb Bourenkov, Josip Vukusic, Ran Friedman, Jan Stake, Thomas Schneider and Gergely Katona

Author Affiliations

University of Gothenburg, the Chalmers University of Technology, the European Molecular Biology Laboratory Hamburg Outstation and Linnaeus University