From the Journal: American Journal of Physics

WASHINGTON, April 21, 2022 – It is well known that global warming is causing sea levels to rise via two processes: thermal expansion, when water expands because of its increased temperature, and melting of land-based ice, when meltwater flows into the ocean. Less known, regarding the latter, is the nuanced phenomenon of gravitational pull. When a large ice sheet begins to melt, global-mean sea level rises, but local sea level near the ice sheet may in fact drop.

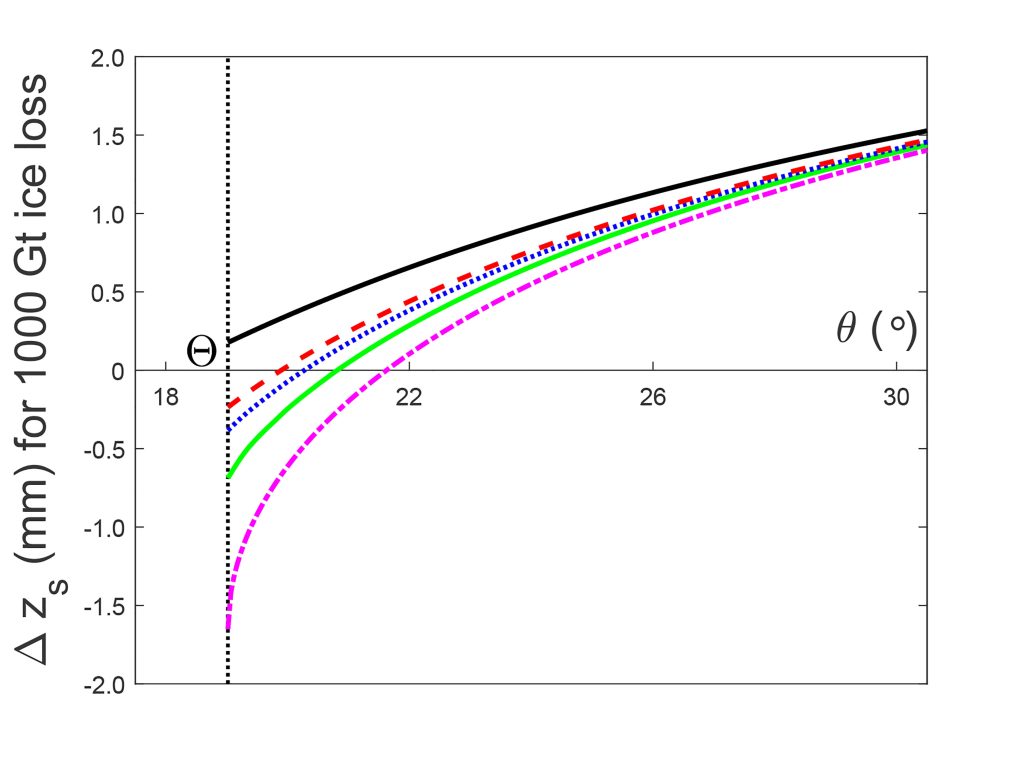

In American Journal of Physics, by AIP Publishing, a researcher from Saint Joseph’s University illustrates this effect through a series of calculations, beginning with a simple, analytically tractable model and progressing through more sophisticated mathematical estimations of ice distributions and gravitation of displaced seawater mass. The paper includes numerical results for sea level change resulting from a 1,000-gigatonne loss of ice, with parameter values appropriate to the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets.

“If the meltwater comes from Greenland, then sea level far from Greenland rises by more than average, but sea level at the Greenland shore actually drops,” said author Douglas Kurtze. “This is at least partially because of how the loss of that ice changes the gravitational pull of the ice sheet.”

A massive ice sheet attracts seawater, raising a mound in sea level around the land on which the ice rests. When the ice melts into the ocean, the global-mean sea level rises.

But the removal of ice mass weakens the gravity of the sheet, thus lowering the mound. In some cases, the lowering of the mound height may be greater than the rise in global-mean sea level, causing local sea level near the ice sheet to drop.

While this cause for nonuniformity in sea level change was recognized and systematically investigated as early as the 1880s, contemporary scientists created sophisticated, detailed models including other important considerations, such as changes to the earth’s rotation and alterations in the shape of the solid earth, when mass, like water and ice, is rearranged on the surface.

“My contribution here is to go in the opposite direction, making a model that is so drastically simplified that it can be used as an example in undergraduate courses,” said Kurtze. The gravitational pull phenomenon “is a fascinating consequence of basic physics, and a great example of just how complex the earth system is – and how well geophysicists can make sense of that complexity.”

Kurtze said he was inspired to develop his model after hearing a radio interview with Jerry Mitrovica, a Harvard professor of geophysics and renowned expert in glacial isostatic adjustment.

###

For more information:

Larry Frum

media@aip.org

301-209-3090

Article Title

Gravitational effects of ice sheets on sea level

Authors

Douglas A. Kurtze

Author Affiliations

Saint Joseph's University

American Journal of Physics

ABOUT THE JOURNAL

American Journal of Physics is devoted to the instructional and cultural aspects of physics. The journal informs physics education globally with member subscriptions, institutional subscriptions, such as libraries and physics departments, and consortia agreements. It is geared to an advanced audience, primarily at the college level. Contents include novel approaches to laboratory and classroom instruction, insightful articles on topics in classical and modern physics, apparatus, and demonstration notes, historical or cultural topics, resource letters, research in physics education, and book reviews.

ABOUT AAPT

AAPT is an international organization for physics educators, physicists, and industrial scientists—with members worldwide. Dedicated to enhancing the understanding and appreciation of physics through teaching, AAPT provides awards, publications, and programs that encourage teaching practical application of physics principles, support continuing professional development, and reward excellence in physics education. AAPT was founded in 1930 and is headquartered in the American Center for Physics in College Park, Maryland.