Wide-field-of-view imager capable of detecting soft X-ray emissions that occur whenever solar winds encounter neutral gas -- including the Earth, Moon, Mars, Venus, and comets

From the Journal: Review of Scientific Instruments

WASHINGTON D.C. July 28, 2015 — Solar winds are known for powering dangerous space weather events near Earth, which, in turn, endangers space assets. So a large interdisciplinary group of researchers, led by the U.S. National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) set out to create a wide-field-of-view soft X-ray imager capable of detecting the soft X-ray emissions produced whenever the solar wind encounters neutral gas.

This week in the journal Review of Scientific Instruments, from AIP Publishing, the group describes developing and launching their imager, which centers on “Lobster-Eye optics,” as well as its capabilities and future applications in space exploration.

The group’s imager was inspired by simulations created about a decade ago by Tom Cravens and Ina Robertson at the University of Kansas, both of whom are now involved in this work, which demonstrated that the interaction between the solar wind and the residual atmosphere in Earth’s magnetosphere could be imaged in soft X-rays.

By way of background, on the sun, wind plasma flows continuously from all latitudes and longitudes — occupying the entire heliosphere and interacting with a neutral gas. This “solar wind” consists primarily of protons, but also contains a flux of high-charge-state heavy ions. When these ions interact with the gas, many undergo charge-exchange reactions and acquire an electron in an excited state, which causes the high-charge-state ions to emit soft X-ray photons.

It’s precisely these sorts of soft X-ray emissions that the group’s imager is designed to detect.

What are “Lobster-Eye Optics”?

Lobster-Eye optics refers to an optical element used to focus soft X-rays, developed by the University of Leicester in the U.K. and Photonis Corp. in France and inspired by the eyes of the eponymous epicurean crustacean.

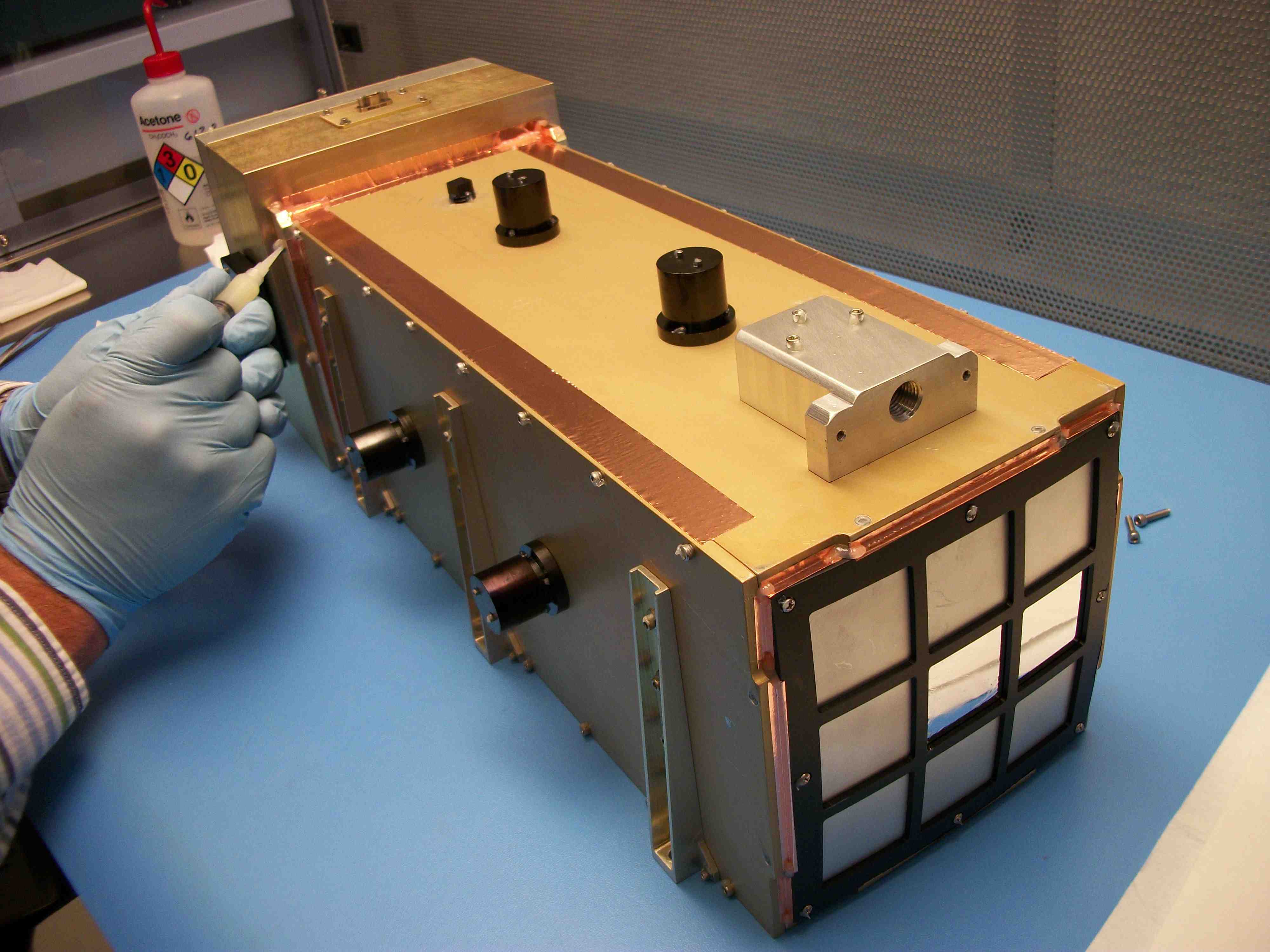

The optical element “consists of an array of very small square glass pores 20 microns on a side curved like a section of a sphere, with a radius of 75 centimeters,” explained Michael R. Collier, an astrophysicist working for NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center and lead author of the paper. “Our imager operates on the same principle as the lobster eye, which is how it got its name, by focusing soft X-ray photons onto a plane located at half the radius of the sphere.”

What’s the significance of a wide-field-of view imager in space? “It takes us one step closer toward global solar wind and magnetosphere imaging capabilities,” Collier said. “And it also represents taking a theory, in this case all of the calculations and simulations of physical phenomena, and successfully applying it to a useful scientific capability.”

To this end, globally imaging the solar wind’s interaction with the Earth’s magnetosphere will enable tracking the flow of energy and momentum into the atmosphere. “Because all of the energy that powers dangerous space weather events near Earth comes from solar wind, this capability allows us to better protect our space assets — particularly geosynchronous spacecraft, such as those that carry cell phone signals,” he added.

In terms of applications, the European Space Agency and Chinese Academy of Sciences are already making plans for a mission called the “Solar Wind Magnetosphere Ionosphere Link Explorer,” a.k.a. SMILE, that will include a wide-field-of-view soft X-ray imager featuring Lobster-Eye optics. “The goal of this mission is to perform global imaging of the solar wind and magnetosphere interaction — something that has yet to be achieved,” said Collier.

What’s next for the group? “These soft X-rays are observed anywhere in the solar system that the solar wind encounters neutral gas—including the Earth, Moon, Mars, Venus, and comets,” Collier noted. “So, in the future, we’ll explore the applicability of our technique within the context of missions to other planets.”

The group’s technique is also easily adapted to nanosatellites such as CubeSats — which boast a form factor ranging from 1 to 10 kilograms and are described in canonical units of 10 x 10 x 10 cm — and will “enable low-cost missions with a high science return,” said Collier.

###

For More Information:

Jason Socrates Bardi

jbardi@aip.org

240-535-4954

@jasonbardi

Article Title

Authors

M.R. Collier, F.S.Porter, D.G. Sibeck, J.A. Carter, M.P. Chiao, D.J. Chornay, T.E. Cravens, M. Galeazzi, J.W. Keller, D. Koutroumpa, J. Kujawski, K. Kuntz, A.M. Read, I.P. Robertson, S. Sembay, S.L. Snowden, N. Thomas, Y. Uprety and B.M. Walsh

Author Affiliations

NASA, The University of Leicester, University of Kansas, University of Miami, CNRS/INSU, Siena College, The Johns Hopkins University, and the University of California, Berkeley