Faster identification of fish sounds from acoustic recordings can improve research, conservation efforts

From the Journal: The Journal of the Acoustical Society of America

WASHINGTON, March 11, 2025 – Coral reefs are some of the world’s most diverse ecosystems. Despite making up less than 1% of the world’s oceans, one quarter of all marine species spend some portion of their life on a reef. With so much life in one spot, researchers can struggle to gain a clear understanding of which species are present and in what numbers.

In JASA, published on behalf of the Acoustical Society of America by AIP Publishing, researchers from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution combined acoustic monitoring with a neural network to identify fish activity on coral reefs by sound.

For years, researchers have used passive acoustic monitoring to track coral reef activity. Typically, an acoustic recorder would be deployed underwater, where it would spend months recording audio from a reef. Existing signal processing tools can be used to analyze large batches of acoustic data at a time, but they cannot be used to find specific sounds — to do that, scientists usually need to go through all that data by hand.

“But for the people that are doing that, it’s awful work, to be quite honest,” said author Seth McCammon. “It’s incredibly tedious work. It’s miserable.”

Equally as important, this type of manual analysis is too slow for practical use. With many of the world’s coral reefs under threat from climate change and human activity, being able to rapidly identify and track changes in reef populations is crucial for conservation efforts.

“It takes years to analyze data to that level with humans,” said McCammon. “The analysis of the data in this way is not useful at scale.”

As an alternative, the researchers trained a neural network to sort through the deluge of acoustic data automatically, analyzing audio recordings in real time. Their algorithm can match the accuracy of human experts in deciphering acoustical trends on a reef, but it can do so more than 25 times faster, and it could change the way ocean monitoring and research is conducted.

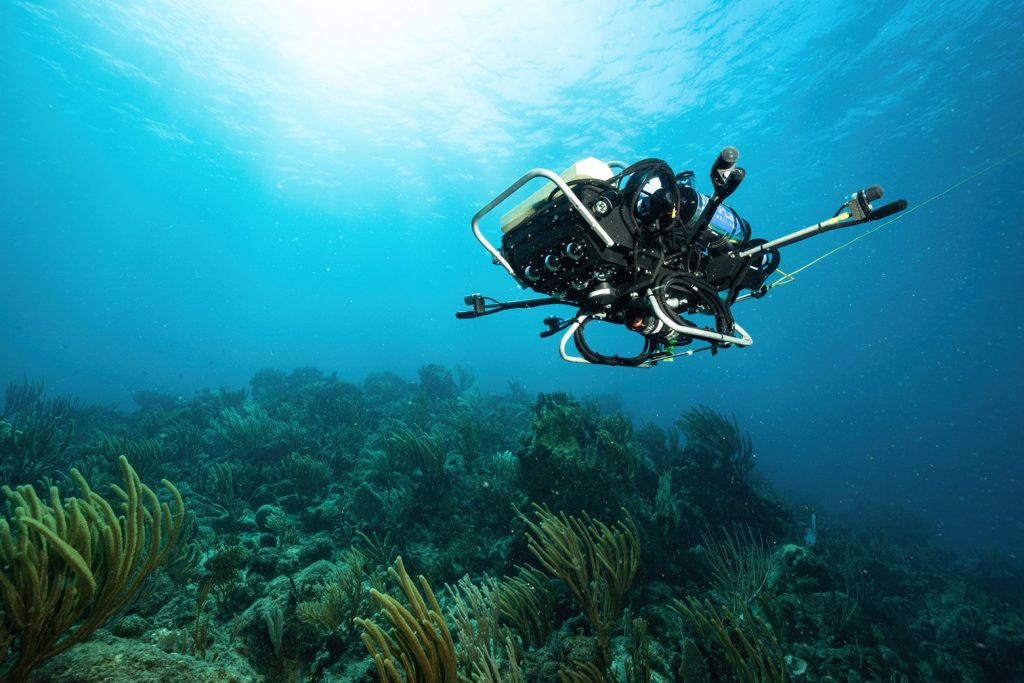

“Now that we no longer need to have a human in the loop, what other sorts of devices — moving beyond just recorders — could we use?” said McCammon. “Some work that my co-author Aran Mooney is doing involves integrating this type of neural network onto a floating mooring that’s broadcasting real-time updates of fish call counts. We are also working on putting our neural network onto our autonomous underwater vehicle, CUREE, so that it can listen for fish and map out hot spots of biological activity.”

This technology also has the potential to solve a long-standing problem in marine acoustic studies: matching each unique sound to a fish.

“For the vast majority of species, we haven’t gotten to the point yet where we can say with certainty that a call came from a particular species of fish,” said McCammon. “That’s, at least in my mind, the holy grail we’re looking for. By being able to do fish call detection in real time, we can start to build devices that are able to automatically hear a call and then see what fish are nearby.”

Eventually, McCammon hopes that this neural network will provide researchers with the ability to monitor fish populations in real time, identify species in trouble, and respond to disasters. This technology will help conservationists gain a clearer picture of the health of coral reefs, in an era where reefs need all the help they can get.

###

Article Title

Authors

Seth McCammon, Nathan Formel, Sierra Jarriel, and T. Aran Mooney

Author Affiliations

Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution